Important Leaks Indicate That Lebanese Authorities Sought Spyware

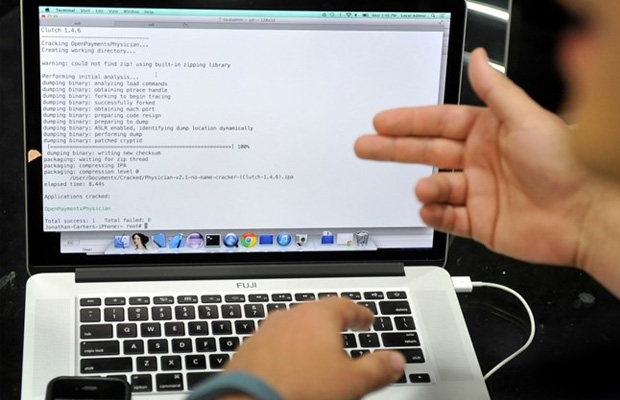

A hacking suite for governmental interception, right at your fingertips. That is how Italy-based spyware company Hacking Team describes its Galileo Remote Control System, billed as a way to “bypass encryption, collect relevant data out of any device and keep monitoring your targets wherever they are, even outside your monitoring domain.” In a twist of irony, HT was itself the victim of a mass hack in July. Termed a “corporate enemy of the Internet” by Reporters Without Borders in 2013, the company had repeatedly denied selling its products to repressive regimes. Entrepreneurial hackers, unsatisfied with these denials, resorted to dumping a treasure trove of 400 GBs worth of data onto the company’s own Twitter feed – renamed “Hacked Team.”

In among these leaks was correspondence with the intelligence branch of the Lebanese Army, General Security and the Cyber Crimes and Intellectual Properties Bureau – all seeking to purchase Galileo.

While these emails have been shared among activists online – the Global Voices Advocacy warns Angry Birds lovers that HT exploited holes in its software to track users during a demo for the Internal Security Forces – there has been no public confirmation by these agencies of whether they are using this system to monitor Lebanese citizens.

When asked on Twitter whether reports that it had paid an initial down payment of over $1 million to HT for the system were true, the Army chose to block rather than answer Lebanese journalist Mahmoud Ghazayel.

“I tried to get a feedback from the Army about this matter, because it concerns my privacy, especially after the evidence that the program sold to Lebanon can be used to bug almost every electronic device connected to the Internet,” he says.

Perhaps even more concerning is the lack of condemnation from civil society actors. Haquna, the Arab Alliance for Internet Freedom, gathered a roundtable of media and technology specialists to release a statement calling on the Lebanese government to not use spyware on citizens. But it took effort, according to Nizar Zakka, the secretary-general of iJMA’, under whose umbrella Haquna operates.

“You see this document about the Lebanese Army having this intelligence software – nobody dared write a word about it,” he says.

“We had to fight to get this press release out, and a lot of people who were with us in the meeting told us they didn’t want to put their names on [it].”

While those at the meeting cited an unwillingness to speak while the Army was battling ISIS on the border, the general lack of engagement with digital rights is aided by the confusion over the legal landscape in Lebanon – especially as there is no specific law governing the Internet.

Little to no transparency from the ISF branch that deals with cybercrimes, the Cyber Crime Bureau, only adds to this confusion. It has been variously accused by activists of being an illegal body, preventing access to lawyers, summoning under false pretenses and using threats of detainment to obtain self-censorship pledges. Repeated attempts by The Daily Star over several months to contact the CCB for comment on any of the above were unsuccessful.

According to The Legal Agenda’s Ghida Frangieh, the CCB was set up by a service memorandum. That means it was an internal decision by the ISF, whereas by law the creation of a unit within the police requires the approval of the Cabinet.

Legality aside, the CCB is also accused of being politicized. Frangieh describes it as “a major tool for influential people … to file complaints against bloggers, journalists and anyone criticizing them.”

Karim Hawa, for example, was detained for four days after sharing an article on Facebook accusing a minister of signing a contract with a company that had Israeli ties.

Activist and journalist Hayat Mirshad refused the bureau’s summons on libel charges after using social media to criticize MTV’s Tony Khalife over his views on “silencing women who are victims of domestic violence.”

Lack of transparency has led some activists to question how the bureau obtains cases, however, according to SKeyes’ Firas Talhouk, the truth is less nefarious. The CCB he says, is an implementary body, “obligated to deal with the complaint when it is passed down to them from the court.”

This means, activists say, any case that so much as mentions the Internet.

“Prosecutors don’t understand what Twitter, and Facebook and blogs mean because most of them belong to a generation that was not raised with the Internet,” Frangieh says.

Regardless of how cases reach the CCB, it is how they are handled that raises the most ire.

Back in April, MARCH – which has set up a legal hotline (70-235-463) to advise those called before the CCB – held a meeting in conjunction with the Beirut Bar Association regarding threats to freedom of expression.

During the discussion, MARCH’s president, Lea Baroudi, criticized the CCB for summoning people as though they were criminals for expressing opinions online.

The NGO called for individuals to be allowed a lawyer during questioning, to know what they were accused of before presenting themselves, to not be detained overnight for questioning and to not sign any pledge.

This was backed up by the president of the Bar Association, Georges Jreji, who said “the invitation for a cup of coffee is an issue we will not take lightly;” referring to the bureau’s habit of luring people in for a ‘chat over coffee’ – something Talhouk says has negative connotations for Lebanese who remember how the Syrian intelligence operated.

ISF representatives at the meeting however, dismissed allegations that the bureau was acting illegally by denying access to a lawyer.

The truth of the matter is hard to pin down. According to Frangieh, “the current culture, whether with the judges or with police stations, is that lawyers cannot attend the investigation – they can come into the police station but they cannot go inside [the room].”

This viewpoint was reinforced by Talhouk, who says that lawyers cannot enter the room during the “initial” interrogation.

“Once the suspect leaves the room the first interrogation is over and a lawyer can be present.”

Frangieh, however, points to Article 32 of the Criminal Procedures Law that states: “The person being interrogated may ask for the assistance of a lawyer during the interrogation.” She argues that the security forces ignore this article for their own convenience.

For Talhouk’s part, he says that individuals have the right to a phone call and the right to be examined by a doctor before and after the interrogation. They are also not obligated to sign any pledge.

While knowing your rights is difficult, having them respected is more so. Karim Hawa was called in for questioning by being told the cellphone he had purchased was stolen – only to be detained for sharing a link on Facebook.

Others have had more success. Mirshad was able to resist the bureau’s summons because she was aware that “in the event of a lawsuit against a journalist, he or she is not to be questioned by judicial police, but by a judge in the presence of an attorney.”

But the law for journalists doesn’t cover bloggers such as Gino Raidy, who was summoned over a complaint by a private company, accusing him of promoting other platforms while denigrating theirs.

The bureau attempted to coerce Raidy to sign a pledge, saying he would not write about the company again. He refused.

Instead he wrote his own pledge including “the preamble to the Lebanese constitution,” which guarantees freedom of expression.

It is not so clear cut, however. Haquna’s Zakka takes a much more forgiving view of the bureau’s work.

Being called in to provide a statement in a dispute is a “normal process,” he says. In the case of one individual slandering another or a company online, there must be some kind of agreement to prevent further damages until the matter is settled in court.

This court however, should be a civil court not a criminal one, activists insist. According to Talhouk, this was also something the bureau’s head, Suzanne al-Hajj, agreed with. She has been quoted by multiple sources as saying the bureau should not be dealing with defamation cases.

Her viewpoint on monitoring for terrorist activity however, has raised concerns. She has been quoted as saying the bureau was using advanced monitoring techniques. This was first mentioned at last year’s Arab IGF conference in Beirut, where, according to Talhouk, Hajj said, “Lebanon had entered the cyberwar against terrorism.”

The open-ended nature of the statement has raised concerns over what lines the bureau has for respecting the privacy of Lebanese Internet users. Haquna recently set up a committee to call for more transparency after the leaks revealed the intent to use the Galileo system.

“Everybody wants to protect Lebanon … but the best way to protect Lebanon is to keep Lebanon free,” Zakka says.

Attempts by The Daily Star to confirm the purchase, use and scope of the Galileo system were unsuccessful, a reflection of the lack of transparency that has caused so much unease among activists.

“We are scared because all the human rights violations go under the pretext of national security,” Zakka says.

© 2024

© 2024

0 comments