Technology Startups Collect Billions Of Dollars And Sit On The Sidelines

Niklas Östberg’s startup has raised so many rounds of funding that he has almost lost track.

“I think officially we’re probably on Series, oh, did we do H maybe?” says Östberg, cofounder and CEO of Delivery Hero, an online food-ordering service. Series H turns out to be the right answer. Delivery Hero periodically receives what Östberg calls “small” investments of $5 million to $20 million from individual investors. It gets hard to remember which round an investor joined.

Delivery Hero, four years old, has already raised more than $1 billion in financing. “I don’t think that the rush for an IPO is there any more,” Ostberg says. “I think we could probably raise another billion without a problem.”

A few years ago, the ability to draw this kind of cash would have put Delivery Hero on par with the largest private tech companies like Twitter, which raised $1.2 billion across 8 funding rounds before going public in late 2013. Now, however, Delivery Hero is just one of a growing number of startups that start collecting larger amounts of capital earlier and keep going longer.

Uber, Flipkart and Xiaomi have each raised well over $1 billion in funding to date. Pinterest hit that milestone just this week, announcing a $367 million Series G round of funding with plans to raise as much as another $211 million more on top. Other prominent startups like Snapchat, Lyft and Airbnb are closing in on the billion-dollar funding mark as well.

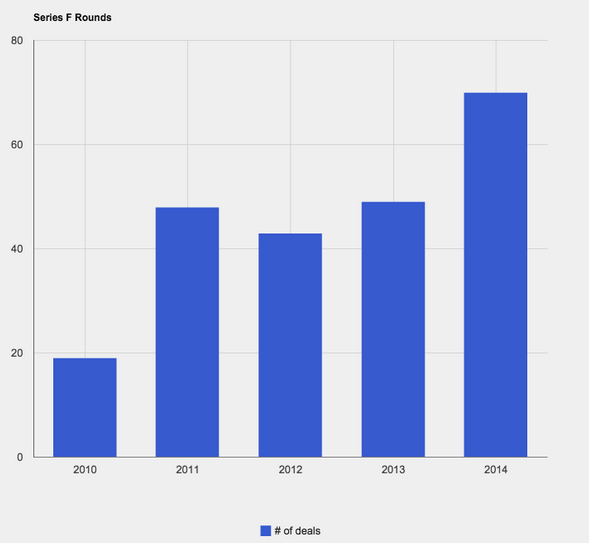

In 2014, tech companies announced 70 funding deals that were labeled Series F or higher, up from just 19 comparable late-stage funding rounds in 2010, according to data provided by CB Insights, a venture capital database. According to the researcher, there are now 10 tech companies with valuations of at least $1 billion that have also raised $1 billion or more in funding.

They’re delaying the old coming-of-age rituals like that senior who hangs around high school just a little too long. Where a Series C or a Series D round was once considered the last stop before an initial public offering, more startups are going into six rounds or more of venture capital funding.

When a startup announces an 8 or 9-figure funding round, it’s often met with a flabbergasted response online. Yet, it’s somehow easier to understand why a service like Uber, which invests in drivers, insurance, regulatory issues, customer service and marketing, might need to raise large sums of money than it might be for, say, Snapchat or Pinterest. After all social networks can grow to hundreds of millions of users with minimal resources — WhatsApp and Instagram each had fewer than 100 employees when they were acquired by Facebook.

“If you’re Snapchat, could you possibly spend a half billion dollars on your technology? The answer is probably not,” says Harry Weller with a laugh. Weller is a general partner at New Enterprise Associates, which has backed Uber and Groupon. Instead, all that money is intended to help the startup raise its profile and compete for talent and acquisitions with larger competitors. “It gives you dexterity. It gives you weaponry to compete with the likes of Facebook.”

With investors throwing around money like this, who needs a public offering? The higher valuations stems from what some investors might frame as an excess of caution. The public markets, which host potential troubles from research analysts to hedge-fund managers with short fuses, are unforgiving. Executives and VCs alike are reluctant to push a company into public life with less than $100 million in revenue or evidence that their earnings won’t jump up and down from quarter to quarter.

“They’re not going public yet because their [business] models still have the volatility of an adolescent,” says Weller. “These are bigger companies in terms of revenue than we’re used to, like an Uber, but the maturity in volatility isn’t there yet.”

Uber is reportedly expected to post $10 billion in net revenue this year, significantly more than Twitter generated during its first full year as a public company. But it’s arguably able to navigate the constant regulatory hurdles, executive troubles and fierce competition better without the watchful eye of Wall Street. The same concerns ring true for similarly disruptive businesses like Lyft and Airbnb.

Both venture capital investors and institutional investors have taken to pouring ever greater sums into superannuated startups in search of greater returns than they would receive from more mature businesses in the public market. That trend has only been amplified by record low interest rates, which are unlikely to rise before June.

The Valley’s financial Peter Pan complex doesn’t stop at taking VC money. Some more established startups like Uber and Box have taken to raising large debt financing rounds to further boost their cash pile and delay a public debut even longer. This approach tends to work best when the company is far enough along in its lifespan to have a strong, recurring revenue model that boosts confidence in its ability to pay back the debt. For smaller startups, though, taking on debt can be particularly risky as shown recently by the fallout for tech news publisher GigaOm.

The appeal of signing on for more debt, says Weller, is that startup founders don’t have to give away even more stock to venture capitalists. “From a bank’s perspective, they only worry about the ability to pay it back,” Weller says.

A rep for Pinterest declined to comment on this story. A rep for Uber did not immediately respond and Snapchat declined to comment.

Östberg, for his part, looks at his company’s $1 billion war chest as a way to have enough money to acquire other companies to bolster his own. He argues that staying private has allowed Delivery Hero to “beat some of the public companies” for acquisitions because the latter may feel constrained by shareholder pressure. And he has no plans to change that dynamic any time soon.

Via Mashable

© 2024

© 2024

0 comments