What Is DNS Hijacking?

Keeping your digital property safe from hackers is hard enough on its own. But as WikiLeaks was reminded this week, one hacker technique can take over your entire website without even touching it directly. Instead, it takes advantage of the plumbing of the internet to siphon away your website’s visitors, and even other data like incoming emails, before they ever reach your network.

On Thursday morning, visitors to WikiLeaks.org saw not the site’s usual collection of leaked secrets, but a taunting message from a mischievous group of hackers known as OurMine. WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange explained on Twitter that the website was hacked via its DNS, or Domain Name System, apparently using a perennial technique known as DNS hijacking. As WikiLeaks took care to note, that meant that its servers weren’t penetrated in the attack. Instead, OurMine had exploited a more fundamental layer of the internet itself, to reroute WikiLeaks visitors to a destination of the hackers’ choosing.

WikiLeaks severs have not been hacked. There have been two types of internet infrastructure (DNS) attacks. Always use HTTPS or our .onion.

— Julian Assange ? (@JulianAssange) August 31, 2017

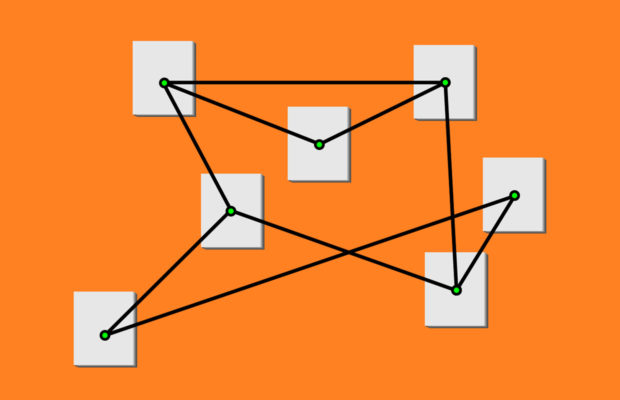

DNS hijacking takes advantage of how the Domain Name System functions as the internet’s phone book—or more accurately, a series of phone books that a browser checks, with each book telling a browser which book to look in next, until the final one reveals the location of the server that hosts the website that the user wants to visit. When you type a domain name like “google.com” into your browser, DNS servers hosted by third parties, like the site’s domain registrar, translate it into the IP address for a server that hosts that website.

“Basically, DNS is your name to the universe. It’s how people find you,” says Raymond Pompon, a security researcher with F5 networks who has written extensively about DNS and how hackers can maliciously exploited it.

“If someone goes upstream and inserts false entries that pull people away from you, all the traffic to your website, your email, your services are going to get pointed to a false destination.”

A DNS lookup is a convoluted process, and one that’s largely out of the destination website’s control. To perform that domain-to-IP translation, a your browser asks a DNS server—hosted by the your internet service provider—for the location of the domain, which then asks a DNS server hosted by the site’s top-level domain registry (the organizations in charge of swathes of the web like .com or .org) and domain registrar, which in turn asks the DNS server of the website or company itself. A hacker who’s able to corrupt a DNS lookup anywhere in that chain can send the visitor off in the wrong direction, making the site appear to be offline, or even redirecting users to a website the attacker controls.

“All of that process of lookups and handing back information are on other people’s servers,” says Pompon. “Only at the end do they visit your servers.”

In the WikiLeaks case, it’s not clear exactly which part of the DNS chain the attackers hit, or how they successfully redirected a portion of WikiLeaks’ audience to their own site. (WikiLeaks also used a safeguard called HTTPS Strict Transport Security that prevented many of its visitors from being redirected, and instead showed them an error message.) But OurMine may not have needed a deep penetration of the registrar’s network to pull off that attack. Even a simple social-engineering attack on a domain registrar like Dynadot or GoDaddy can spoof a request in an email, or even a phone call, impersonating the site’s administrators and requesting a change to the IP address where the domain resolves.

DNS hijacking can result in more than mere embarrassment. More devious hackers than OurMine could have used the technique to redirect potential WikiLeaks sources to their own fake site to try to identify them. In October of 2016, hackers used DNS hijacking to redirect traffic to all 36 of a Brazilian bank’s domains, according to an analysis by the security firm Kaspersky. For as long as six hours, they routed all of the bank’s visitors to phishing pages that also attempted to install malware on their computers. “Absolutely all of the bank’s online operations were under the attackers’ control,” Kaspersky researcher Dmitry Bestuzhev told WIRED in April, when Kaspersky revealed the attack.

In another DNS hijacking incident in 2013, the hackers known as the Syrian Electronic Army took over the domain of the New York Times. And in perhaps the most high-profile DNS attack of the last several years, hackers controlling the Mirai botnet of compromised “internet-of-things” devices flooded the servers of the DNS provider Dyn—not exactly a DNS hijacking attack so much as a DNS disruption, but one that caused major sites including Amazon, Twitter, and Reddit to drop offline for hours.

There’s no foolproof protection against the kind of DNS hijacking that WikiLeaks and the New York Times have suffered, but countermeasures do exist. Site administrators can choose domain registrars who offer multi-factor authentication, for instance, requiring anyone attempting to change the site’s DNS settings to have access to the Google Authenticator or Yubikey of the site’s admins. Other registrars offer the ability to “lock” DNS settings, so that they can only be changed after the registrar calls a site’s administrators and gets their ok.

Otherwise, DNS hijacking can enable a full takeover of a website’s traffic all too easily. And stopping it is almost entirely out of your hands.

Via WIRED

© 2024

© 2024

0 comments