Mosquitoes May Just Like Some People Better

Ah, spring, when a young outdoorswoman’s fancy lightly turns to thoughts of insect bites. While I do own DEET-based repellant, my main trick for avoiding bites is inviting my friend Allie along on hikes or camping trips — when we return, she’s covered in mosquito bites, and I’m scot-free. Yes, mosquitoes really do like some people better than others, and a new paper from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine suggests there’s a genetic component to that preference.

In the study, scientists compared how attractive sets of twins were to mosquitoes, using groups of identical and fraternal twins. The identical twins were more similarly attractive to mosquitoes than the fraternal twins, according to the study, published in PLOS One. That’s probably due to genetics — identical twins share more genes than fraternal ones. Those genes are important for determining body odor, which is part of how mosquitoes seek targets. Granted, it’s a pretty small study — just 18 identical twins and 19 fraternal ones. The researchers chose twins because they’re “a good way to discover if a trait is heritable,” study author James Logan, a senior lecturer at the London School, writes in an email.

Scientists spend a lot of time thinking about what makes people attractive to biting insects, since those insects can spread diseases like malaria, West Nile virus, chikungunya, and dengue, says Anandasankar Ray, an assistant professor of entomology at the University of California-Riverside. It’s helpful to know how female mosquitoes — only females hunt, and only if they’ve mated — go about selecting their targets, so that better repellants can be designed.

The system by which mosquitoes find a meal is fairly complex, Ray says (he wasn’t involved in today’s study). “Mosquito navigation is a very sophisticated series of maneuvers,” he says. “When you think of a space shuttle being launched toward the ISS, you have phases: launch, the rocket disengaging, stage separation, then docking. In the same manner, a mosquito flying toward a human has stages.”

Flying upwind requires energy; the only time a female mosquito will do it is if she detects a plume of carbon dioxide — humans exhale about two liters of breath every minute, Ray says, and 4 percent of it is carbon dioxide. This activates the mosquito, making the insect more sensitive to skin odor. When mosquitoes are only a few meters away from a potential meal, they switch from navigating by carbon dioxide to skin odor — that’s generally when they make a beeline for exposed skin, Ray says. Humidity and body temperature may play a role as well. Once the pest lands, it tastes the skin of its next meal using hairs on its feet. That gives scientists a lot of places to mess up mosquitoes’ abilities to find their meals.

Much of what we know about mosquito attraction has to do with carbon dioxide. People who exhale more of it tend to be more attractive to mosquitoes — so people who’ve been exercising or have larger body masses are pretty appealing targets.

That’s not all that drives mosquitoes, though. People who are infected with malaria are also more appealing to them, and some previous research suggests that skin bacteria — which produce some components of body odor — may also play a role. But some of a person’s individual smell is pure genetics, and that’s what today’s study was meant to test.

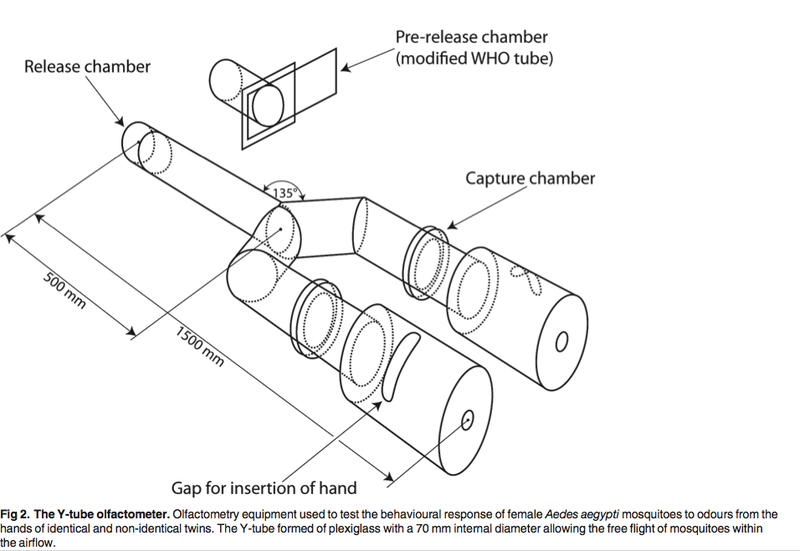

Scientists placed participants in pairs, then used a tube with a Y-shaped design. At the top two points of the Y was tasty, tasty skin — a hand from each of the two participants — and at the bottom point was the mosquito. The scientists measured how often mosquitoes picked each person to feed on, in order to get a sense of who was most attractive to the bugs, and who was least. They then compared attractiveness between sets of twins, and found the identical twins were closer in attractiveness levels — suggesting that the genes that control body odor may indeed play a role. The heritability values they found suggest similar levels to height and IQ, Logan and his team write in the paper, though the small sample size means they must be cautious about the comparison.

It’s also not clear from the study design whether the variation is due to attractive or repellant chemicals on the participants’ skin. Future studies may focus on trying to link specific attractive or repellant odors — Logan’s group has already discovered a few — to genetics. A major place to start searching is the major histocompatibility complex (MHC), a set of genes that code for proteins on the surfaces of cells. Linking odors from the MHC to mosquitoes’ behavioral responses could lead to new mosquito repellants.

And that’s pretty important, Ray says. Right now, the major ways to avoid being bitten are DEET, a chemical that repels insects, and mosquito bed nets. New methods are needed, as some mosquitoes are now resistant to DEET. Ray’s lab is developing new ways to try to keep the bugs from biting, and they’re not the only ones working on the problem.

“With my mosquito work, I always get this question: why am I more attractive than my wife?” Ray says. “That’s one of the most interesting questions.” Today’s work on body odor may help provide clues, so scientists can finally answer it.

Via TheVerge

© 2024

© 2024

0 comments