World’s Oldest Life Form Could Help Fight Antibiotic Resistance

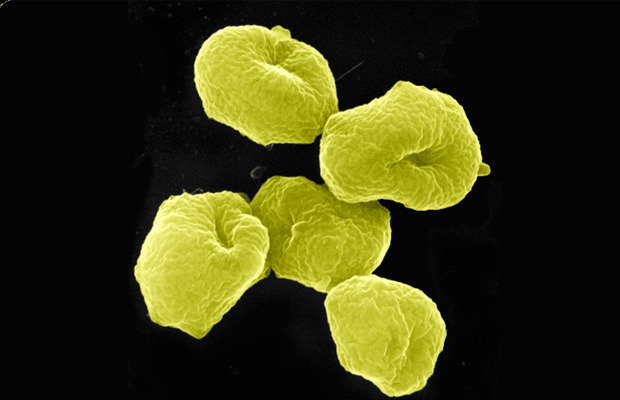

If you’ve ever taken a biology course at or above the high-school level, you’ve probably encountered the term Archaea in a passing sense. You won’t have heard much detail about these microbial lifeforms, because their importance to the overall web of life is mostly historical; as the Latin implies, archaea are possibly the most ancient form of life there is, a slightly different take on the idea of a bacterium.

They’re often called extremeophiles because they seem to have survived almost exclusively in extreme environments like deep sea vents, acid rivers, and the mouths of volcanoes. Still, nobody really knows quite why bacteria took over the vast majority of the world and not archaea, other than to say that that’s just how things fell out. It’s a small and unsatisfying corner of evolutionary biology that has gone relatively unstudied, given its historical importance, but new work could make the microbes very relevant indeed. Scientists from Vanderbilt University have discovered that we may be able to make archaea an ally in the war on infectious bacteria.

The scientists were looking into a relatively unknown antibiotic molecule first discovered in a virus, when they noticed something odd: the gene coding for this molecule is actually found all over the web of life. They found their gene in bacteria, fungi, even plants, but the most surprising find was in archaea — though they were thought not to interact very much with other forms of life, it seems that archaea really do fight with bacteria from time to time. Not only have bacteria been found encroaching on extreme environments, but archaea are now known to live in milder places as well; these ancient contenders need protection as much as anybody else, and looking into archaea’s potentially unique innovations could help scientists stay ahead of the bacterial curve.

Modern defenses against bacteria are almost all derived from bacteria or fungi; these are molecular weapons that were first created by other life forms eons ago, and science has merely hijacked them for its own purposes. Archaea, by being fundamentally alien to bacteria’s evolutionary history, could be a uniquely useful source of new antibiotic molecules. This research helps explain how archaea are able to live in the same environments as bacteria, and thus compete with them at least partially for resources — as with anything else, the issue is decided through struggle.

There are some really great education campaigns out there these days, aimed at teaching people how not to doom the human race by overreacting to a sniffle. Still, even when used properly, ballooning life expectancies alone will keep the flood of antibiotics strong. There’s a lot of energetic research going on to avert this crisis, and now we have one more avenue for possible breakthroughs. Archaea don’t cause any diseases in humans, which is part of why they’ve been ignored for so long, but this ability to walk through our ecosystems untouched could also make them extremely useful. Even if they don’t provide some unique weapon molecule for us to use, archaea themselves could be useful tools for when scientists want to minimize the side-effects of using a biological agent.

Archaea are a fascinating and still poorly understood facet of the tree of life, but their importance could be huge. They may very well have more in common with the ultimate common ancestor, the first replicator from which every living thing in history derived, than any other life form today. That alone ought to make them interesting. Their ability to assist in the fight against infection is what could make them important.

© 2024

© 2024

0 comments